History

Introduction

Throughout its history the heart of New York City's housing problem has been the lack of affordable housing for the working and middle classes. The history of the Cooperative Village on the Lower East Side is the story of a revolutionary idea that came to fruition through the cooperation of individuals, unions, and government.

Among New York City neighborhoods the Lower East Side was well known for its overcrowded and substandard housing for the immigrant working classes. This situation had been a growing cause of concern among residents, reformers and city government throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, but there were few incentives for private capital to invest in affordable housing for these groups. The situation became acute in the post-World War I period. Little construction had occurred during the war due to shortages of labor, fuel and materials. High interest rates and soaring construction costs during the post-war period led to a general slowdown in new housing developments. Rents skyrocketed, evictions rose, and rent strikes were common.

In 1926 New York State passed the Limited Dividends Housing Companies Act with the goal of promoting the construction of more affordable housing developments. The primary features of this legislation were the right for municipalities to condemn land for large-scale construction, 20-year exemptions from municipal real estate taxes, and rents regulated and limited by the newly created Housing Board. Upon signing the new bill into law, Governor Alfred E. Smith, who had grown up in Lower East Side tenements, stated,

In approving this bill I do so with the sincere hope that it may prove the beginning of a lasting movement to wipe out of our state those blots upon the civilization, the old dilapidated, dark, unsanitary, unsafe tenement houses that long since became unfit for human habitation and certainly are no place for future citizens of New York to grow in.

The law provided incentives to encourage private capital to construct affordable housing, however once built there would be little profit in these types of regulated low-income housing projects. Private investors were slow in taking on such projects. But the incentives did appeal to others. Civic-minded and progressive men were actively working to remedy the housing situation. The unions in particular were interested not only in improving the working conditions of its members but also in their general welfare. They were inspired by democratic-socialist ideas and social movements that grew in response to industrialism and the harsh working conditions in factories and sweatshops. The Lower East Side had been a hotbed of progressive politics and unionism. Men who pioneered the idea of cooperative housing - men such as Abraham E. Kazan - grew up as eyewitnesses to the wretched tenement conditions.

A slowdown in construction during World War II created another period of housing shortage, especially for the returning GIs and their families. In 1949, the federal government passed the National Housing Act. Under the provisions of Title I of this Act, the federal government would assist municipalities with clearing slums, planning, reconstruction and neighborhood rehabilitation. In New York, Robert Moses led the Committee on Slum Clearance, which was responsible for planning and coordinating Title I projects. The committee and in particular, Robert Moses came under much criticism for the way the various Title I projects were handled. But by the end of the Title I subsidies, thirteen cooperatives had been constructed in New York.

Amalgamated Clothing Workers

In 1927 the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union, founded by Sidney Hillman, was the first union to organize and sponsor a housing cooperative under the 1926 housing law. Abraham Kazan, then the president of the ACW's credit union was appointed as president of the Amalgamated Housing Corporation, which became the first limited dividend housing company in New York City. Their first project was the Amalgamated Houses near Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx, which expanded over the years into the multi-building Amalgamated-Park Reservoir houses. The Pioneer Cooperators, as the first generation was called, developed a model cooperative community with extensive cultural and educational programs. They then turned their attention to providing housing for union members on the Lower East Side and in 1930 completed construction on the Amalgamated Dwellings, which provided 230 units. This Art-Deco style building, located on Grand Street was designed by architects Springsteen and Goldhammer, and has been cited frequently for its simplicity and elegance.

East River Housing

Recognizing the need for additional housing a memorandum from Abraham Kazan and the United Housing Foundation was written on May 19, 1950, which proposed an extension of the recently completed Hillman Houses. The East River Housing Corporation was incorporated on November 28, 1950. In its initial planning stages, the East River Houses were known as the Corlears Hook Project (324 page PDF). This project would clear the last of the slums and tenements from Corlears Hook. The International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union, headed by David Dubinsky, was invited by the United Housing Foundation to become the financial sponsor of the new cooperative which the union agreed to after reassurances that the mortgage loan would be insured by the Federal Housing and Home Finance Agency. The Edward A. Filene Good Will Fund provided financial support for the initial planning stages.

East River Houses was also the first project in NYC to qualify for slum clearance funds under Title I of the Federal Housing Act. Under the provisions of Title I the Federal government paid two-thirds and the city government one-third of the write-down value of the land acquired for the development. The land was acquired by the city by condemnation at a price of $5,900,680. On the same day the East River Housing Corporation purchased the land at public auction for a price of $1,049,240. The balance of $4,851,440 was divided between the federal government ($3,234,293) and New York City ($1,617,147). (Refer to the East River Development Expenditure Analysis to see how these funds were spent.)

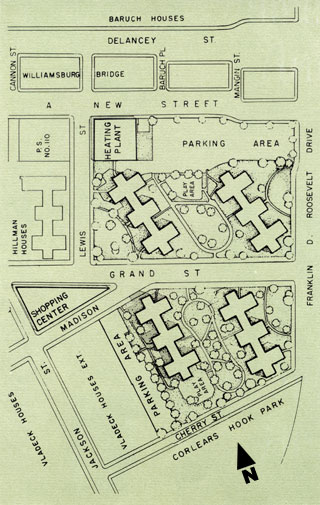

Thirteen acres of slums, south of Lewis Street to the FDR Drive and fanning out from the Williamsburg Bridge to Cherry Street were cleared to make way for the East River Housing site. At the groundbreaking ceremony on November 21, 1953 David Dubinsky addressed an audience that included thousands of garment workers.

Many of us are here today as natives returning to the scenes of our childhood. Fifty-three years ago, the ILGWU was officially organized to war against the sweatshop. That war has continued for more than two generations. Now, half a century later, we return to the place where our union was born. We have wiped out the sweatshop. We return to wipe out the slum.

The first of the four apartment buildings completed -two are 21 stories tall and two are 20 stories - were dedicated on October 22, 1955. (All of the buildings were available for occupancy in 1956.) These were the tallest reinforced concrete apartment structures in the United States at the time of their construction. The development provided 1,672 units with the average rental of $17.00 a room per month. The buildings were placed on the site in a direction to give each apartment the maximum amount of sunlight, and wherever possible a view of the river. Approximately ten acres were devoted to playgrounds, gardens and parking facilities. The architects responsible for the design were George W. Springsteen and his associate, Herman J. Jessor. These architects were also responsible for designing several other cooperatives in the city.

In addition to the apartment buildings East River Houses includes a central power plant and a two and a half story shopping center located on a triangular shaped block directly opposite two of the Hillman buildings on the south side of Grand Street. A useful feature of the shopping center is a 1,000-seat auditorium. The auditorium, located on the upper floor of the center, has been used for cooperative and community activities of all kinds. Kitchen facilities, small meeting rooms and offices are also available. The East River Corporation owns the shopping center and derives income from the rental of the offices and stores.

Applications for membership in the cooperative were first received on August 22, 1952. If there was ever any doubt that moderate income families were in desperate need for decent housing, it was dispelled by the long lines of people stretching for blocks, who were waiting to fill out applications for apartments which would not be completed for many years. Nearly five thousand applications were received for 1,672 apartments. Those who became members of the cooperative came from all parts of the city and surrounding area. Most significant is the fact that two-thirds came from the East Side. The applicants who were living on the site of the project and who would have to be relocated were given first consideration for apartment selection.

Legally there were no income restrictions on prospective cooperators. However, as the purpose of the cooperative was to supply housing, which families of low and moderate incomes could afford income became a significant factor. Many of the first residents were primarily Jewish or Italian (a reflection of the ethnic make-up of the garment unions) but throughout the years the racial and ethnic makeup has become more diverse.

Cooperative Principles

The cooperatives grew out of the principles of self-help and democratic rule. In the early twentieth century, the idea of cooperative apartments was as different in concept from the old tenant-landlord relationship as the buildings were from the tenements that they had replaced. People could provide themselves with housing by combining their financial resources. Each stockholder would invest a proportionate part of the required equity in the cooperative, and each would have an equal share in the development. Each member would have one vote in the affairs of the organization. There was no landlord; collectively the tenants would serve as their own landlord.

The rent, or carrying charges, which covered the expenses of the organization, would be shared proportionally and kept as low as possible. If at the end of the year there were a surplus, it would be returned to the tenant-owners as a refund or a rent rebate. If on the other hand the expenses exceeded income, it would be up to the tenant-members to increase the carrying charges. To discourage speculation, when a member decided to move he was required to offer his stock for repurchase to the Corporation.